(Part 2 from Uncle Don)

German (Prussian) Mennonites who lived in the Vistula River delta in northern Prussia found life increasingly difficult in the last half of the 18th century. Religious persecution, high taxes, demands for young men to serve in the military, and the threat of war motivated them to find a new home. In God’s providence, events on the political scene opened the door for those Mennonites and other people groups to emigrate to an area of southern Russia north of the Black Sea known today as Ukraine.

Catherine II, also known as Catherine the Great, was named Princess Sophie Friederike Auguste von Anhalt-Zerbst-Dornburg at her birth on May 2, 1729. She was the daughter of Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst, who was a member of a German ruling family and a general in the Prussian military. Sophie was groomed throughout her childhood to be the wife of some powerful ruler in order to improve the socio-economic position of the von Anhalt family. Through the influence of some of her mother’s wealthy relatives, arrangements were made for Sophie to marry her second cousin and the prospective Russian tsar, Peter of Holstein-Gottorp. She entered Russia in 1744, and was received into the Russian Orthodox Church on June 28, 1744, with the name Catherine Alexeyevna. She was betrothed to marry Peter the next day. The wedding occurred in St. Petersburg on August 21, 1745, following her sixteenth birthday.

The marriage of Catherine and Peter was unhappy. Peter was grossly immature and lacked ability to manage his own affairs, let alone the government of Russia. However, the Empress Elizabeth died on January 5, 1762, and Peter ascended to the throne of Russia as Emperor Peter III. Recognizing his inability to govern and weakness of character, Catherine conspired with others to conduct a coup to remove him from the throne. She appealed to the military to protect her, arranged for Tsar Peter’s arrest, and forced him to sign a letter of abdication from the throne. Peter died eight days later (July 17, 1762). Russian Orthodox clergy ordained her the sole occupant of the throne and her coronation occurred on September 22, 1762. There was additional juicy intrigue—but that is not the subject of this essay!

Before Catherine became Empress, Russia had attempted to colonize the southern territory of its empire productively after seizing it from the Ottoman Empire. The area along the lower Volga River was unstable with roving bands of nomadic Kazakhs and Kalmyks making settlement impossible. Catherine and her government wanted to solidify that region as Russian territory. They needed settlers who would turn the land into productive farms and serve as a model for native people in the area. Catherine II approved a new colonization policy and issued a Manifesto on December 4, 1762, inviting people from other European nations to enter and settle in Russian territory. This first Manifesto was stated in general terms and contained few specific policies.

Catherine issued a second Manifesto on July 22, 1763, at the end of the Seven Years’ War, timed perfectly to appeal to Europeans who were weary of warfare and high taxes. Copies of the Manifesto were distributed throughout Europe, but targeted German speaking areas. The second Manifesto was enhanced to make the offer more specific and attractive. The Manifesto promised: 1) transportation to and within Russia; 2) choice of residence and occupation; 3) freedom to practice one’s religion and to construct places of worship; 4) freedom from taxation (30 years in rural areas, 5 years in cities); 5) loans to construct factories; 6) interest-free loans to construct dwellings, purchase livestock and farm equipment; 7) freedom for a colony to write its own constitution and self-govern; 8) duty-free import of personal property; 9) freedom from military conscription and civil service; 10) food rations and transportation to one’s chosen destination; 11) freedom from export duty and excise tax on products exported from Russia (10 years); 12) the right to purchase Russian serfs to work in factories, et al; 13) tax-free markets; and 14) freedom to emigrate from Russia with pro-rated exit fees. Read the Manifesto at: https://www.germansfromrussiasettlementlocations.org/2017/07/on-this-day-22-july-1763-catherine.html.

Catherine’s Manifesto was just what the German Mennonites who lived in the Vistula River basin needed. The first Mennonite immigrants went to the Chortitz region and formed villages consisting only of Mennonite families with Catherine’s agreement. They found life in Russian territory to be difficult and a number of the settlers died during the first harsh winter. German immigration slowed, but did not end. In 1786, Catherine extended a summons to Mennonites in the Vistula River Valley. She promised: 1) religious toleration; 2) exemption from military duty; 3) free use of the crown forests; 4) 175 acres of land for each family; 5) exemption from taxation for ten years, no Crown dues, and minimal annual fee per acre; 6) free transportation to their new homes; 7) A $250 loan per family; 8) daily financial income until the first harvest; 9) full control over their own churches and schools; 10) self-government; and, 11) a provision that they could not proselyte the Russians.

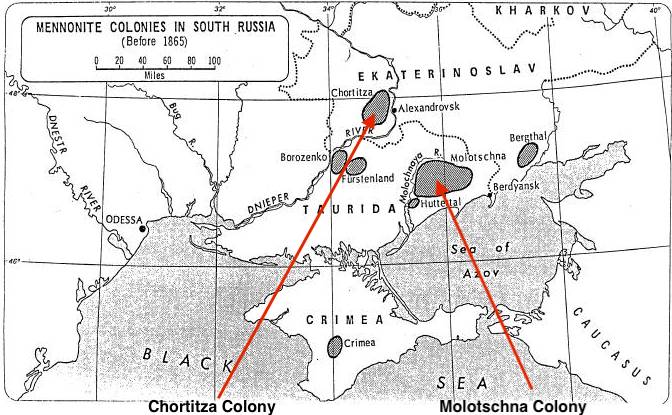

Catherine the Great died on November 17, 1796. She was succeeded by her son, Paul I. Mennonites in Russia sought a reaffirmation of the provisions of Catherine’s Manifesto. Paul granted that in a Privilegum published on March 22, 1800. As a result, 362 Mennonite families moved from the Vistula delta to Russia between 1802 and 1806. The first Mennonite colony in south Russia was the Chortitza Colony, established in 1789 on the banks of the Dnieper River northwest of the Sea of Azov on land taken from the Ottoman Empire. A second, larger colony was established farther south, approximately 110 miles north of the Black Sea, in 1803. The new colony was known as the Molotschna (Molochna) Colony. A few families from Chortitza moved to Molotschna, but the colony was developed primarily by Mennonite families from the Vistula region, et al. Over time, approximately sixty villages were established in the colony.

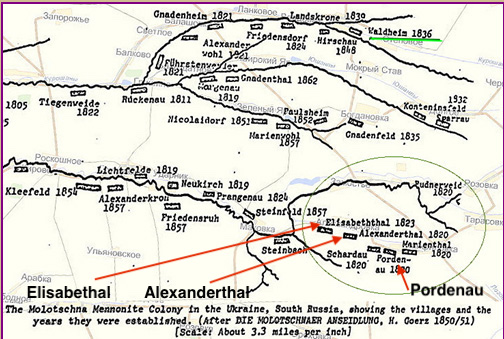

The earliest recorded ancestor of the Toews family was Franz Tows (later spelled Toews). He was born in Altenau, West Prussia, in 1780. His son, Franz Toews (II), was born in Heubeden, West Prussia on April 3, 1812. Franz Toews II moved to the Molotschna Colony at an unknown date before the birth of his first child, Jacob F. Toews (my great-grandfather), on September 5, 1861. All of his children were born in a village called Pordenau (Pardenau). Helena Lohrenz (my great-grandmother) was born in Alexanderthal (Alexanderwohl, Alexandertal), the village west of Pordenau on June 19, 1968. Jacob F. Toews married Helena Lohrenz in Mountain Lake, MN, on October 30, 1888. Peter Franz (my great-grandfather) was born in Elisabethal, the second village west of Alexanderthal, on September 5, 1861. He became the father of Agatha Franz, Oma’s mother.

The first map below identifies the locations of the Chortitza Colony and the Molotschna Colony in South Russia (Ukraine) in 1852. The three villages where our ancestors were born and lived are identified in the second map of the Molotschna Colony. More about village life in the next essay.

Very interesting. Thanks 😊