Our second trip out included materials for building a 16×24 frame building. We got the studding up for a slant roof shed and nailed up the outside walls. One wall was seven feet high, and the other was nine feet high. This and a shack at Henry Berg’s homestead were the first buildings in the community. Back to Wolf Point we went. At first we followed buffalo tracks until finally there were wagon tracks. Later we made round trips in one day, milking our cows at 3 a.m. and leaving them, returning about 11 p.m. and milking again.

The third time out Kathrina came along, and we quickly put roofing up, lapping it over and nailing on slats in order to be enclosed the first night. The horses were on one side and we were on the other, with posts in between. The cows were behind the horses, and the chickens in the coop. We had a grass floor. From Minnesota we thought that the horses had to be inside. Later we left them outside, but those first nights we had them inside with us. We tried to sleep, but Kathrina didn’t sleep a wink. The horses and cows kept moving and rubbing on the sides all night. So we decided they could stay outside. We put up a wall and a floor to separate the house part from the barn part. We had only a two-burner kerosene stove for cooking, with no other heat.

The next morning we had six inches of snow. When we got up and looked outside, everything was white as far as we could see. The sky and the land all seemed one. During the day we would put everything outside to air out and put it back inside for the night. We went back to Wolf Point for more supplies. All the homesteaders that had temporarily stayed in Wolf Point had left their livestock in town. When we got the cows it took over two days of walking. By this time, from our homestead we could see other homesteaders’ shacks, tents and livestock all around us.

We were able to get a heavy cast-iron range, but Kathrina got hurt while unloading it and had to be in bed several days. There was no chimney, so we just put the pipe through the wall. I needed to go back to Wolf Point and wanted another lady to stay with her, but couldn’t get anyone. So she had to stay alone. I hurried as fast as I could. We had to bring all the wood along from Wolf Point for our stove. The second year the coal pits were opened to the north of us, and we went there by wagon for coal. For washing clothes we had a tub and washboard, which we set on a box outside. We bought a gallon of syrup when we left town, plus some canned meat, potatoes and flour. My brother-in-law Peter came here when we did and stayed with us for a few weeks in the one room. He did homestead 160 acres a few years, but sold it.

For water we went ¾ mile west and found a spring. We shoved away the little frogs and filled our water barrels with the spring water. At home we would unload the barrels from the wagon. Sometimes they would tip over and spill. Then we had to go back again to refill the barrel. The other homesteaders that were close by also got their water at the same spring. We put up some boards and sank them into the spring so that the water could seep through the cracks but keep the frogs out. It was about three foot by three foot and about three foot deep. Then we had good, clean water. The well on the farm was dug in about 1920, when a man came around the homesteads with the equipment. We pumped water by hand, but it did not need to be hauled from the spring. Later we got a windmill to pump for us. The well was 106 feet deep and had very good water.

The first summer we had a small garden. I broke a small patch of ground with the one-bottom plow. Every three rounds I would pick up the sod and put the seed potatoes under the sod. I had nothing to dig with or to level the ground. The horses would tramp it smoother. As the rain came and the potatoes grew, the ground would bulge up. When they were ready in the fall, I never had to dig. Just lifted up the sod and picked up the potatoes. They lasted us all winter.

The first summer we plowed up two acres with a 12-inch hand plow and four horses. Kathrina would lead the horses the first round, and I would hold the plow, which I had never done before. Oh, that was just about impossible. After I broke two acres, I gave up. No more that way. So I disked it, since that’s all I had. I bought one gallon of flax seed and one pail full of oats. Well, we had no drill to seed. Kathrina would drive the horses with the wagon and I would stand in the wagon and hold the gallon of flax in one hand and throw the seed over the strip of plowed land. There was quite a strong west wind, so it spread very well and quite even. The I took the disk and drove over it again. Then it rained, and all the seed came up and grew. In the fall, since I had no binder, I cut it with the grass mower and raked it. I loaded the flax on the hayrack and drove to Jake Toews’ where they were threshing. I threshed 9½ bushels out of that load. I thought that was very good from one gallon of seed, but I had lost a lot while cutting it. I cut and hauled in the oats on the wagon for feed for the cows.

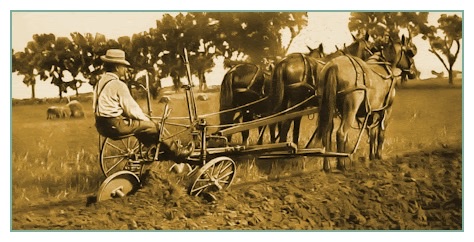

The second year I bought a 16-inch sulky plow with a seat and one more horse from Henry Fast for $80. We went to town and mortgaged our team of horses to get the money. Then I got a drill and made a packer out of old wheels. I used five horses for the sulky plow and plowed 28 acres. It was the only way I could get away from the single-bottom walking plow we had brought from Minnesota. The next year it was too dry to go on. After harvest I went to the bank to pay off the note and the banker couldn’t find it. After much searching it was found in a cubby hole in his desk, and I paid it off.

During the late 20s we had very dry years with about 15-17 bushels per acre. In 1930 we had only one bushel per acre, but we harvested anyway and had seed for next year. In the bad years I bolted a combine reel onto the mower, and this is the way I harvested the crops because the grain was only four to six inches high. As a rule, crops were cut with a binder and then threshed. In 1928 combines came out, which made farming much more efficient.

Most did not harvest and just opened the gates and let the cattle graze. For about five years it was very dry. Many homesteaders gave up and left. I thought of it too, but a banker encouraged me by loaning me money with a “pay as you can” policy. At one point the banker even offered to pay our taxes. Like everyone else in the community, I had to borrow money. Those years I borrowed $16,000. The banker would not accept any payment the first two years, but insisted that the small profits be put back into the farm. The third year the banker asked me how much money I had after harvest. “$4,000,” I said. The banker, Mr. Anderson, gave me half and put $2,000 down on the loan payment. In five years all the loan was paid off. This was the only time I borrowed money to run the farm. We had thought about giving up and moving to Oregon to work in the fruit, or back to Minnesota. But there was little land for sale and prices were high, so we decided to stay in Lustre. The banker said that if I had left, ten or more others would have given up and also left. If we stayed, others would also be encouraged to stay. That is why he had helped us with the loan.